Univ.-Prof. Dr. Friedlich Leblhuber*

The term „Dementia“ includes a group of diseases in which affected people have a limited mental function concerning memory, orientation, speech, perception and the ability to learn. Dementia affects about 1,5% of 65-69 year-olds and the risk of developing the disease rises radically with age. Alzheimer’s is the most common neurodegenerative disease in the ageing population and is responsible for about 60-70% of all dementias.

The probability of developing Alzheimer’s disease rises with age, but other risk factors include obesity, high blood pressure, Diabetes, mental inactivity, lack of social contacts, smoking, lack of movement, a bad diet and depression. The disease was named after the Doctor Alois Alzheimer, who first documented the characteristic changes in the brain of a patient with dementia back in 1906.

Dying nerve cells

In the case of Alzheimer’s disease, nerve cells die off in certain brain sections. Furthermore, the sites of communication between nerve cells, the synapses, are lost. Nevertheless, we need intact synapses to effortlessly transfer and process information. The neurotransmitter acetylcholine is also needed to transfer information, which is produced in the cells that die off in Alzheimer patients. As a consequence, too little acetylcholine is produced. This leads to a dysfunction in the processing of information and ultimately results in memory loss. The death of nerve cells is accompanied by the production of unusual proteins, which are deposited between nerve cells (amyloid plaques) and within nerve cells (tau fibrils). These were the first microscopic changes observed in the brains of Alzheimer patients by Alois Alzheimer in 1906.

The role of the intestines

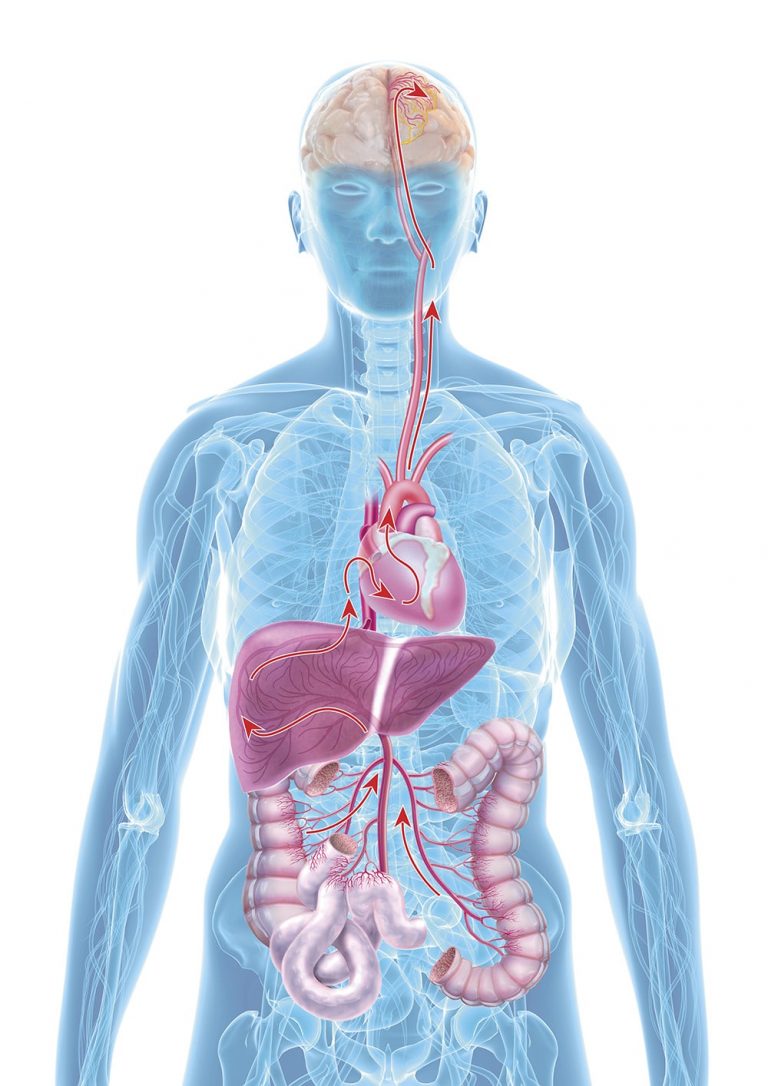

The exact cause of Alzheimer’s is not yet clear, however, there is increasing evidence that the so-called gut-brain-axis plays a central role: Both of these organs communicate with each other in many ways, e.g. directly via nervous connections or also via immune messengers, intestinal microbiome signals and intestinal hormones. New studies also show that the intestinal microbiome partially regulates the transfer of information (neurotransmission) to the central nervous system. Scientists assume that the age-related changes of the intestinal microbiome and the intake of drugs induce a dysbiosis, in other words, a damaged intestinal flora, and result in a silent inflammation of the intestine.

The aftermath is a damaged, porous intestinal barrier with the inflammation possibly spreading throughout the entire body (silent systemic inflammation). Finally, the inflammation reaches the brain and then brings on cognitive degeneration.

Clinical studies confirm: If the intestinal barrier is destroyed (Leaky Gut), bacteria and their metabolic products can leave the intestines and deposit themselves in different parts of the body and can cause damaging effects (bacterial translocation). A Leaky Gut can be confirmed, among others, by measuring the amount of calprotectin in faeces, whereas a high concentration can indicate a damaged intestinal barrier. In a clinical study, the faeces of 22 Alzheimer’s patients were analysed, of which 73% had a Calprotectin concentration above the norm (> 50mg/kg). This upholds the hypothesis that faecal Calprotectin is the result of a Leaky Gut and leads to an unnoticed („silent“) systemic inflammation process – ultimately also in the brain.

Probiotics and dementia

Recently, 55 patients with cognitive deficits were examined at the Kepler University Clinic as to whether probiotics have a positive effect on the inflammable processes in the body.

At the beginning of the study, faeces and blood samples were taken from patients in order to study the composition of the intestinal flora as well as to determine the various inflammation parameters. The results show that the inflammatory markers in the faeces (measured with the marker S100A12) as well as in the blood (Neopterin) both correlated with one another. Furthermore, an increase of the marker CRP (C-reactive protein, increases during inflammation) was determined without any clinical signs of an inflammation. These results all point towards the „silent inflammation“ being a cofactor in the development of dementia.

Afterwards, all participants received a probiotic with new scientifically tested, anti-inflammatory bacteria strains for 28 days.

After all the patients had finished the intake of the probiotics, their faeces and blood were analysed once more: There was a significant increase of Neopterin and Kynurenin – both markers that indicate an increased activity of the immune system (combatting inflammation). These recent studies are giving us first clues that probiotics can have a positive effect on inflammations in our bodies in Alzheimer’s disease and cognitive impairment. These results need to be corroborated in larger studies to prove the effectiveness of probiotics against dementia. Moreover, the prevention of dementia through probiotics is a future field of study: Hereafter, the development of dementia could possibly be delayed or even prevented by strengthening the intestinal microbiome.

*Univ.-Prof. Dr Friedlich Leblhuber is the emeritus head of the neurological-psychiatric gerontology ward at the Wagner-Jauregg State Mental Hospital and now an independent physician of neurology in Linz.