We live in an age in which the number of people who are overweight is rising at an alarming rate. That our society has a serious weight problem has become the norm for us – just like the repeated warnings from medical professionals.

There is no need to look across to the United States, where fast food and XL-sized soft drinks are part of everyday life: the figures here in Europe are already cause for concern. More than 50% of people in Europe are overweight or obese – despite decades of health initiatives.

What is particularly worrying is that more and more children are affected. Statistics from the UK show that around one in seven children (15%) aged between two and 15 were obese in 2022, and this number is only on the rise.

Particularly problematic are the secondary and associated conditions caused by excess body fat and the metabolic changes that come with it. People who are overweight are considered to be at especially high risk of developing metabolic syndrome. This condition is characterised by severe overweight with excess abdominal fat, high blood pressure, raised blood lipid levels and elevated blood sugar levels.

This is not a marginal issue. In the UK, it is estimated that around 20–25% of the population (one in four adults) is affected. The risk of further long-term conditions is also significantly increased: around half of those with metabolic syndrome go on to develop cardiovascular disease later in life, while approximately three-quarters develop type 2 diabetes.

Causes of diabetes & obesity

An unhealthy lifestyle is considered to be the main cause of these worrying lifestyle-related diseases: too little physical activity in everyday life combined with the so-called Western diet. This industrialised way of eating is characterised by excessive consumption of processed foods, meat, fat, sugar and salt – habits we have all become far too accustomed to. So accustomed, in fact, that the question remains whether it is even possible to reverse this trend.

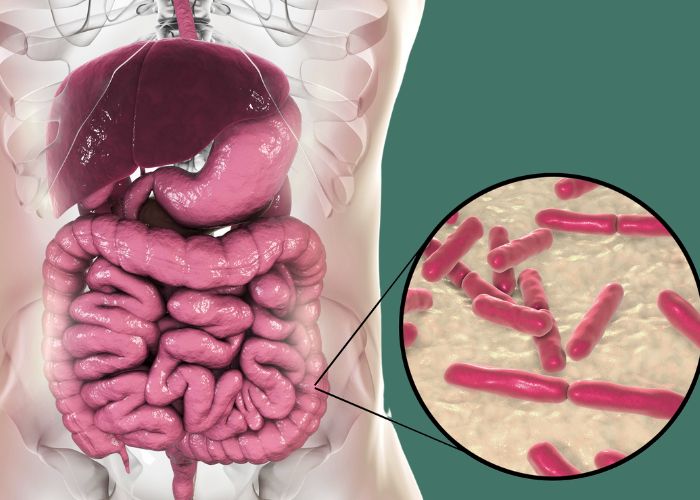

Does the microbiome influence metabolism?

Who hasn’t caught themselves assuming that people who are overweight lack willpower or are simply lazy, because they fail to follow the supposedly effective formula of “fewer calories equals less weight”? In principle, this idea is not wrong: anyone who maintains a balanced energy intake – consuming no more energy than their body uses at rest – will remain slim.

But, as Professor Vanessa Stadlbauer-Köllner, gastroenterologist and hepatologist at the Medical University of Graz, explains: “Obesity is a complex problem, not merely a matter of balancing calorie intake and expenditure.”

Obesity develops through the interaction of genetic predisposition, poor diet, lack of physical activity, stress, environmental influences and psychological factors. While this combination of causes is now largely understood, effective, side-effect-free treatments are still the subject of global research. This is where the microbiome plays a key role.

Stadlbauer-Köllner has been researching the interactions between medication, disease and the gut microbiome for many years and explains the connection as follows: “Our diet, with its excessive amounts of sugar and fat, alters the diversity and composition of our gut bacteria. This, in turn, has negative effects on sugar and fat metabolism – and ultimately leads to weight gain.”

More specifically, endotoxins (bacterial toxins) from the gut enter the body through a damaged intestinal barrier, triggering increased cytokine release and, as a result, systemic inflammatory responses. This creates a negative spiral that can lead to insulin resistance and continued weight gain.

Conversely – and this is also supported by studies – the composition of the microbiome can be improved again through dietary changes and increased physical activity.

More calories from ready meals

To understand the complexity of these relationships, it is important to recognise that when it comes to nutrition, it is not only the number of calories that matters, but also how those calories are processed. In one experiment, healthy participants were given food over a 14-day period containing identical proportions of sugar, carbohydrates, fibre, fat and salt. One group received the food in an unprocessed form, while the other was given ready-made meals.

In the latter group, participants consumed around 500 extra calories per day and gained approximately 1 kg in weight over the two weeks. This clearly shows that highly processed foods lead to increased calorie intake.

“Why this happens has not yet been fully researched. It is likely that our bodies misjudge highly processed foods, or that the feeling of fullness sets in later,” explains Stadlbauer-Köllner.

Weight gain due to the microbiome

Research findings also show that an unfavourably composed microbiome can contribute to excess weight. “This is an indication that the microbiome plays a causal role in weight gain,” says Stadlbauer-Köllner. She is referring to a Harvard study in which the gut microbiomes of human twin pairs were analysed – one twin lean, the other overweight.

The overweight participants showed a significantly reduced diversity and altered composition of gut bacteria, with an excess of so-called Firmicutes bacteria and too few Bacteroidetes bacteria.

To investigate this further, the gut microbiome of the lean twin was transplanted into one group of germ-free mice, while the microbiome of the overweight twin was transferred to another group of mice.

Both groups were then fed the same diet. The groundbreaking finding was that the mice that received the microbiome from the overweight twins gained significantly more weight than those given the microbiome of the lean twins.

Survival mode

This may help to explain why some people lose little or no weight despite changing their diet. “There are individuals with a particular microbiome composition that makes it easier to gain weight when there is an excess of calories. Several hundred years ago, this was a genuine evolutionary advantage, as it helped people survive periods of food scarcity. Today, however, in an era of food abundance in the Western world, it has become a disadvantage.”

It is well known that Firmicutes bacteria are able to extract calories even from indigestible fibre. Bacteroidetes, by contrast, encapsulate unused carbohydrates, allowing them to be excreted in the stool. As a result, the microbiome of an efficient “energy harvester” can extract up to 30% more calories from the same amount of food than the gut bacteria of lean individuals.

These findings highlight the significant potential of the microbiome in the treatment of disorders of fat and sugar metabolism, such as obesity and type 2 diabetes.

Positive effects on metabolism

The primary treatment for obesity is a change in lifestyle, combining dietary changes with increased physical activity. Intermittent fasting can lead to successful weight loss, and the associated health benefits are supported by research. Intermittent fasting not only improves the composition of the microbiome – leading to increased production of anti-inflammatory short-chain fatty acids – but also triggers a “browning” of white fat tissue. Brown fat is associated with a higher basal metabolic rate, which in turn makes weight loss easier.

A recently conducted study involving people with type 1 diabetes (the form of diabetes in which the body produces little or no insulin) even showed that intermittent fasting can reduce the body’s insulin requirements. However, diets such as intermittent fasting are difficult to maintain in everyday life over the long term. Eating is about more than nutrient intake alone; it also fulfils social and psychological needs such as socialising, reward, relaxation and distraction. As a result, only a small proportion of people manage to maintain their new weight in the long term after successful weight loss.

Weight loss injections & stool transplants

“Because the basal metabolic rate is reduced, long-term success tends to be limited. When someone loses a large amount of weight, their entire metabolic situation changes, and they absorb more energy from food than they did before losing weight. This is the well-known yo-yo effect, which is also well documented scientifically,” explains Stadlbauer-Köllner.

It is therefore unsurprising that those affected place their hopes in supposedly “simple” weight-loss solutions such as pills or so-called weight-loss injections, or even opt for surgical interventions such as gastric bypass operations – despite the risk of serious side effects and complications. It should also be remembered that treatment only begins once the problem already exists.

For this reason, the expert believes that prevention at a societal level is at least equally important. “The food industry has a vested interest in conditioning us to foods high in sugar and fat, so that we constantly crave them,” says Stadlbauer-Köllner. “That is why preventive measures are extremely important.”

One topic that has attracted both fascination and unease in recent years is faecal/stool transplantation. Given the sheer number of people affected, the physician sees this less as a suitable form of therapy and more as a way to further explore the links between the microbiome and obesity or diabetes.

To give one example, in a research study, stool from healthy, non-diabetic donors was transplanted into people with diabetes, resulting in a measurable improvement in insulin resistance. In another case, stool from an overweight individual was transplanted into a healthy person, after which the recipient gained weight. As a result, current guidelines now stipulate that only healthy donors may be approved for stool donation.

Probiotics as an effective option

Microbiome changes are very similar across the range of conditions associated with metabolic syndrome. This means that improving the composition of the microbiome represents a promising future treatment approach. Several clinical studies have shown that the use of probiotics can lead to a trend towards weight loss.

In addition, positive effects on BMI, waist circumference, body fat percentage, as well as sugar and fat metabolism have been demonstrated. It has been shown that a treatment duration of six months produces stronger effects than three months, and higher probiotic doses were also associated with better outcomes.

What is now needed is the right step from theory into everyday clinical practice. “There must be consensus recommendations: what diagnostic conclusions can be drawn from the microbiome?” Stadlbauer-Köllner points out. Research must also continue to provide robust clinical data so that microbiome-based treatment using medically relevant probiotics can be included among treatments recognised by social health insurance providers – and therefore made accessible to everyone.