More than digestive helpers

During ancient times, scholars assumed that gut bacteria influence our health in many different ways. Modern medicine has been able to verify such assumptions, and we now know that our gut bacteria choose which nutrients are absorbed by our body and how waste is broken down. They even influence the immune system and regulate our body weight. Hundreds of different bacteria species inhabit our intestines:

An unbalanced gut flora composition – in other words, an increased number of „bad“ and a reduced number of „good“ bacteria – can have a negative impact on our health. Chronic inflammable bowel diseases, food intolerances, allergies as well as psychiatric and neurological diseases can be the result of an unbalanced intestinal flora.

The impact that our microbiome has on our health is still largely unexplored, however many studies are already showing how gut bacteria can affect every part of our organism – even our hormone levels.

Are the intestines our hormonal headquarters?

The intestines and the brain are closely connected via nerve pathways (enteric nervous system), metabolic products of gut bacteria and hormones. For example, the intestines can inform the brain which nutrients the body needs the most. The intestine even produces a whole range of its own hormones („messenger substances“) depending on the composition of the gut flora.

These include the happy hormones dopamine and serotonin, among others, and even the sleep hormone melatonin can be found in large concentrations in the intestines. Hormones influence us in all walks of life, especially during birth, childhood development, puberty as well as during the menopause or andropause (male menopause). Besides the endocrine glands, also known as hormonal glands, that release their secretions into the bloodstream, the microbiome can produce biochemical hormones and play an important role in physical changes.

Furthermore, the interaction between gut bacteria has a significant impact on metabolic diseases such as Type 2 Diabetes or obesity. Unbalanced intestinal flora can also promote inflammatory and auto-immune diseases, the development of tumours and be a decisive factor in the development of endocrinological (hormonal) diseases.

Oestrogen levels out of sync

New studies show that the intestinal microbiome plays a central role in the regulation of oestrogen levels in the body and therefore influences the risk of developing certain hormonal diseases. If the microbiome in the intestines is healthy, our bodies – especially the ovaries – produce just the right amount of the enzyme ß-glucuronidase, which is responsible for the regulation of oestrogen levels. A disruption of our microorganisms‘ home, however, interferes with the activity of this enzyme and results in either an over- or undersupply of oestrogen. Consequently, diseases such as endometriosis, breast and prostate cancer as well as the polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) can develop.

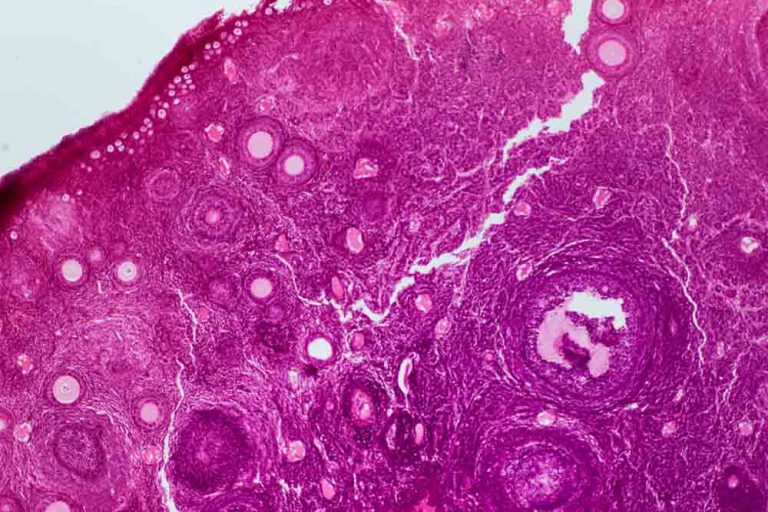

PCOS is the most common hormonal disorder in women of childbearing age, with 4-12% of women in Europe suffering from this disease – incidentally, even male relatives can develop this disease. Women with PCOS show enlarged ovaries with many small cysts on the edges in ultrasound scans. Symptoms typically include absent menstruations, an unfulfilled desire for children, excess weight and even cosmetic problems such as hair loss, increased body hair and blemishes.

The microbiome of patients with PCOS is drastically altered and shows less bacterial diversity.

PCOS often includes an insulin resistance which could result in Diabetes Mellitus Type 2 in the long run. The risk of developing cardiovascular diseases is similarly elevated. The cause of PCOS is the excess of male hormones (androgens) in comparison to the female hormone oestrogen. This imbalance in the hormone system is the result of a genetic predisposition (even if there is not a designated gene for PCOS) together with testosterone levels in the mother during pregnancy – not to mention the microbiome.

Microbiome and PCOS?

We know from high-quality studies that the microbiome can contribute to PCOS associated symptoms by manipulating the metabolism of energy, our body weight and insulin sensitivity. It is also well-known and proven that the intestinal flora is closely linked to – and possibly a cause of – chronic inflammations and an increased permeability of the intestine. The inheritance of certain bacteria could possibly also influence the inheritance of PCOS since no clear genetic cause has been found.

Recently, several Austrian (pilot) studies examined the correlation between the microbiome composition in PCOS patients and that of a healthy control group. The examinations of the microbiome in the faeces of patients with PCOS revealed an altered composition and decreased a variety of bacteria phyla.

Furthermore, researchers were able to determine that several parameters pointed towards a decreased function of the intestinal barrier and towards endotoxemia (note: poisoning caused by the collapse of bacteria in which so-called endotoxins are released from the bacteria and enter the bloodstream).

Increased permeability of the intestinal barrier can have a negative impact on insulin sensitivity, in other words, more insulin is needed which could ultimately lead to diabetes. Even the number of bioavailable androgens increases and disturbs the balance of hormones. Besides an altered microbiome, increased figures of the inflammatory parameter zonulin were found. Zonulin is a marker for intestinal permeability and is linked to a reduced variety of bacteria in the intestines of patients with PCOS.

In summary, there is a fascinating, closely-linked interaction between the microbiome and our (sex) hormones, our immunity and energy metabolism. Studies are trying to determine the exact importance of our microbiome. However, initial results show that the modulation of damaged intestinal flora in PCOS patients could offer a new treatment alternative in the future. Through the targeted administration of probiotics, hormone levels and symptoms of endocrinological diseases can be positively influenced without the side effects of modern medicines. Many studies intend to devote more time and resources to this exciting topic and confirm the far-reaching importance of the microbiome for our health.

Hormones

The word hormone is derived from the old Greek work „hormaen“ which basically mean to drive or activate. The term was first used by the English physiologist Ernest Starling, the discoverer of the digestive hormone secretin. Hormones are produced by so-called endocrine glands and are directly released into the bloodstream – that is how they can influence cells that are far away from the origin of the hormone and therefore act as important chemical messengers between different organs.

A quick summary of the most important hormones

Adrenaline, our fight or flight hormone, helps mobilise our bodies and gives us the additional strength we need in dangerous and stressful situations. This hormone is produced in the adrenal medulla and then released into the bloodstream.

Cortisol is produced in the adrenal cortex and is a stress hormone just like adrenaline. It influences blood vessels as well as our metabolism and is especially important for the electrolyte balance.

Dopamine and serotonin: These hormones and neurotransmitters are responsible for the transmission of electric impulses from one nerve cell to another. They are also known as happy hormones.

Endorphins are the body’s own opiates and act as natural painkillers. These substances also make sure that you stay alert in emergency situations.

Insulin enables our body to store energy. After eating carbohydrates, a healthy body releases insulin which allows sugar to enter the cells where it is then stored and lowers blood sugar levels. If this system is damaged, i.e. too little insulin or an increased cell resistance towards insulin (increased insulin demand), medical treatment is needed.

Melatonin is the hormone that regulates our circadian rhythm and is produced in the pineal gland out of serotonin. Additionally, many other parts of our body, i.e. the intestines, can produce melatonin.

Oestrogen and testosterone: The sex hormones are responsible for women looking like women and men looking like men. They influence our feeling of lust and our ability to reproduce.

Taking a closer look at oestrogen

Oestrogen has many important functions in our bodies. It regulates fat deposition, the fertility of a woman, cardiovascular health, bone formation and cell renewal. Women during their menopause have a dysfunctional oestrobolom – that is the part of the microbiome that depends on the level of oestrogen – as well as an increased risk of cardiovascular diseases, osteoporosis and obesity. In fact, obese people and patients with osteoporosis or cardiovascular diseases were more likely to have an unbalanced intestinal flora. Hence, there is a correlation between these diseases and the oestrobolom. An unbalanced diet and an unhealthy lifestyle can have a negative impact on the oestrobolom. Furthermore, antibiotics and hormonal contraceptives can change the balance of bacteria and levels of oestrogen in our bodies.