The intake of food is essential to human life. However, the question arises whether our „Western Diet“, with all of its industrially produced and processed foods, is really good for us… In the following interview with Mag. Anita Frauwallner, Dr Robert Barring explains the connection between our diet and the microbiome, the fatal consequences an unhealthy diet can have on our health, and the favourite „food“ of the trillions of bacteria that live in our intestines.

Dr. Robert Barring*

Mag. Anita Frauwallner: Countless diseases that are associated with a bad diet are currently on the rise and are becoming an epidemiological problem. Obesity, liver dysfunction, cardiovascular diseases, as well as Type 2 Diabetes and mental illnesses are among these, and we know from extensive research that all of these problems show a change in the intestinal composition of the affected individuals. How does a bad diet present itself clinically?

Dr. Robert Barring: Our body sends us many different signals when we eat unhealthy food. Sadly, these signals are often misunderstood or ignored. I am convinced that some of the many readers here regularly experience the one or the other „outcry“ in their intestines: An unhealthy diet often presents itself as a sugar craving after a meal. Paradoxically, the body feels hypoglycaemic after consuming food. Talking about blood sugar: If our diet causes an imbalance to our blood sugar levels (Note: Easily digestible carbohydrates such as white flour or sugar raise the blood sugar levels rapidly but lower them just as quickly), many patients report a feeling of light-headedness: Besides drowsiness and dizziness, many patients have the feeling that their head is weightless and could float away at any moment. Many others also describe inadequate and permanent fatigue after a meal.

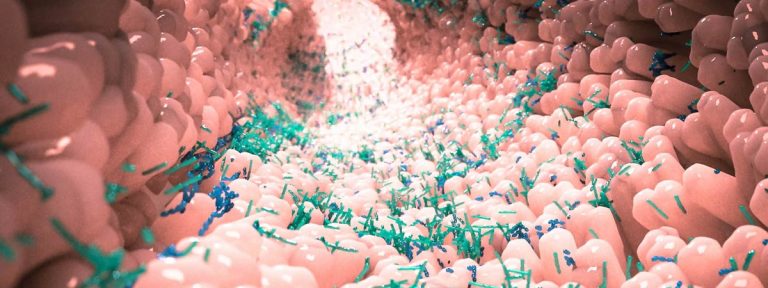

An unhealthy diet leads to significant changes in the intestines and microbiome, which we can diagnose with the help of laboratory diagnostics. The main changes we see are a colonisation with putrid bacteria or the presence of a Leaky Gut. The latter is a porous intestine with an increased permeability for allergens and toxins. This leads to a severe reaction of the immune system and is diagnosed by measuring an increase in zonulin levels.

That being said, food should not make us tired, extremely happy, or make us want to eat more. Food should only satisfy us – and nothing else.

Mag. Anita Frauwallner: Talking about a bad diet – how can we define it for our readers? Or rather: What effect does this have on the bacterial colony in our intestines and how quickly does this happen?

Dr. Robert Barring: Our typical „western diet“ (in other words, the predominant diet in industrialised western countries) is not good for us: Copious amounts of meat, too much sugar in soft drinks and snacks, white flour and – partially hidden – low-quality fats are all a part of our daily menu. Natural foods such as veggies, fibre-rich legumes, fruit, and whole-grain products are often missing. This doesn’t only affect the microbiome, but also the entire metabolism of our intestinal bacteria and gut.

A chronic lack of fibres forces important bacteria to look for another source of food. For example, Akkermansia muciniphila is a helpful bacteria that produces butyrate – more on that later – and is exceptionally important for our intestinal barrier (i.e., our protection against toxins and pathogenic germs): The bacteria in question stimulates the so-called goblet cells in our intestines to produce more mucus that acts as a protective layer for the cells in the intestinal wall. However, if Akkermansia muciniphila are undernourished due to a lack of fibres, they start breaking down this important mucus as a source of food. As a result, this leads to erosions in the intestinal mucosa and tissue damage, which allows pathogens easy access into our organism.

Conclusive evidence shows that the vital diversity of various bacteria species in the intestines is severely reduced in industrialised countries.

In other words, our „modern“ diet does not promote our wellbeing. Instead, it enables the development of diseases. Here’s one frightening example: A study from the USA analysed the effects of fast food on the microbiome and, in particular, the activation of NF-kB (a transcription factor that releases pro-inflammatory substances) in children. The aforementioned factor was significantly increased 1,5 hours after the consumption of a „children’s menu“ and resulted in mediated inflammations in the child’s body. European children show a significantly lower amount of the short-chain fatty acid butyrate and have a drastically different intestinal flora composition: They are home to an increased number of unwanted putrid bacteria, Salmonella, Shigella, and Klebsiella with a reduced amount of health-promoting bacterial species.

Mag. Anita Frauwallner: You are making it very clear that a long-term, unhealthy diet for our intestinal bacteria can have a massive effect on our entire organism: The entirety of the living microbiome is significantly reduced and therefore can’t produce important metabolic products such as hormones and short-chain fatty acids. As a result, permanent inflammation hotspots linger in many people, with severe consequences.

Dr. Robert Barring: Exactly! Many people aren’t aware that the intestines regulate more than just our digestion: A (misguided) microbiome plays a large role in the development of „common mental disorders“ such as depression and anxiety through the gut-brain-axis. In these diseases, the hormones that are responsible for our wellbeing are out of balance: The harmony of serotonin, gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), noradrenaline, adrenaline, acetylcholine, and co depends on our microbiome – whose composition depends on our diet. In other words, if our diet is out of sync, so are our hormones. It is therefore important to always pay attention to the microbiome in patients with mental illnesses and offer support in the form of probiotics, not only psychotherapeutic drugs – especially in children and adolescents.

In such cases, short-chain fatty acids (e.g., butyrate, acetate, and propionate) are of utmost importance. These are produced by the intestinal bacteria and serve the intestinal wall as a source of energy to maintain its protective role. Two especially important bacteria that produce butyrate are the aforementioned Akkermansia muciniphilia and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii. Countless studies have confirmed the correlation between a reduction in these species of bacteria and the occurrence of inflammatory bowel diseases, irritable bowel syndrome, and even colon cancer.

Butyrate even plays an important role outside the intestines: It serves as a source of energy for the brain, more specifically the microglia cells (Note: special macrophages). These cells act as the „garbage disposal“ in our brain by getting rid of toxic substances and deposits. Their activity is mainly determined by butyrate: If there are too little butyrate-producing bacteria in the intestines, the „rubbish“ lies around in our brain. This is an important topic when looking at mental illnesses as well as dementia and Parkinson’s in old age.

Mag. Anita Frauwallner: Our diet and the wellbeing of our intestines with all of its microscopically small inhabitants are inseparable – thankfully, our microbiome can be positively influenced. Studies show that a fibre-rich diet, together with the intake of pro- and prebiotics, is the most effective in restoring balance to our intestines and even our entire organism.

Dr. Robert Barring: Conclusive evidence shows that the vital diversity of various bacteria species in the intestines is severely reduced in industrialised countries. In comparison, traditional small farmers and hunter-gatherer-tribes have a greater diversity of bacteria species in their intestines. The biggest difference can be found in diet and, more importantly, fibre content: The more fibres we eat, the more healthy food the gut bacteria have at their disposal and the better the development of the microbiome. Common intestinal flora colonisation variants can be divided into so-called enterotypes. By increasing the amount of raw food and, therefore, the amount of fibres we eat, we can permanently change our enterotype.

We can promote the colonisation of certain bacteria. Many intestinal bacteria are anaerobic and can’t grow in the presence of oxygen, which is why we can’t grow and ingest them. However, we can boost the growth of these bacteria in our intestines by giving them prebiotics containing fibres such as fructooligosaccharides or acacia. At the same time, special probiotics can treat inflammations, drive out pathogens, and regulate an excessive immune system.

Our diet has the biggest impact on achieving a stable and health-promoting microbiome. To understand the clinical importance of the many connections of the intestinal bacteria with their metabolic products, and our wellbeing, more clinical studies are needed. We need to develop valid testing methods to discover the causes scientifically so that we can help our patients to the best of our abilities.

Mag. Anita Frauwallner: Thank you so much for these exciting insights in your day to day clinical life and functional medicine. Research is so important to us for that very same reason! More precisely, we hope to expand our knowledge about our intestines for the wellbeing of all of humanity.

*Dr. Robert Barring is a specialist in General Medicine, founder, and scientific director of the Institute of Functional and Stress Medicine (IFMS) in Hannover. Functional Medicine looks for the cause of a disease by taking not only acute symptoms into account but also the diet, stress levels, and behaviour of individuals. The diagnosis and treatment also include previous diseases and the intake of medication throughout a patients‘ life. The IFMS offers courses for all medical professions (doctors, alternative practitioners, pharmacists, psychotherapists, etc.).