Your Intestines: The Centre of Health

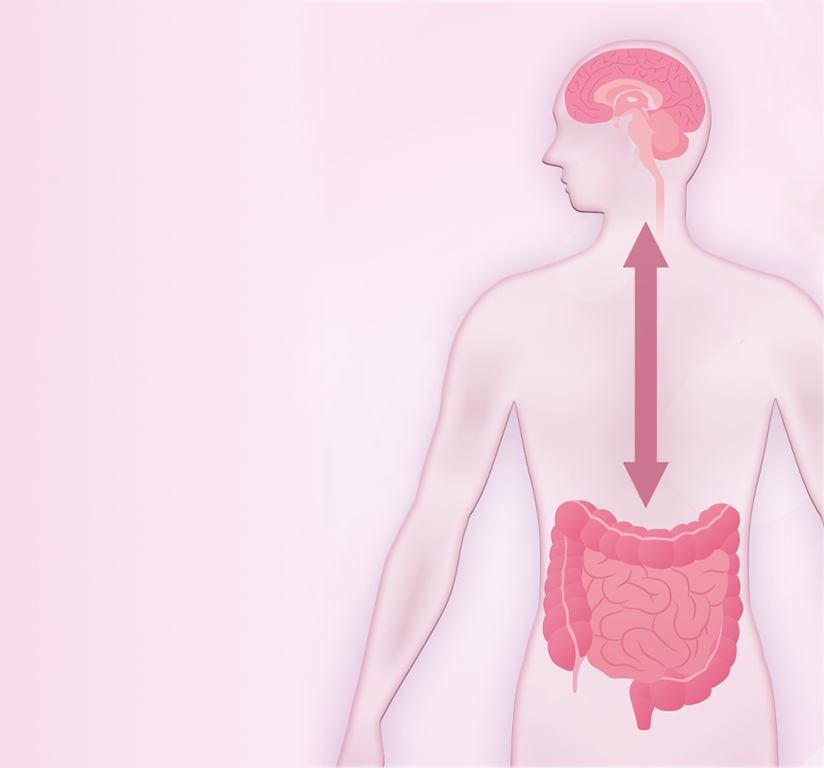

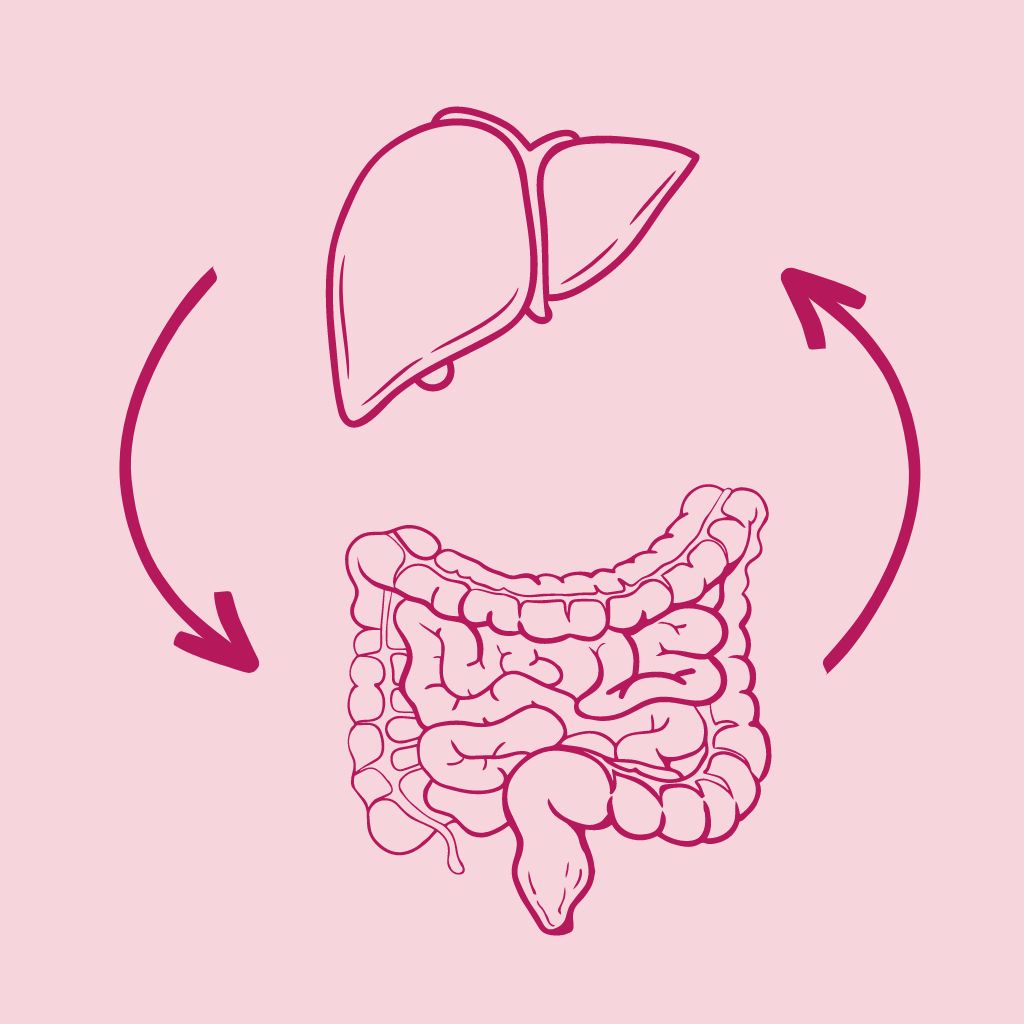

Our bodies are powered by our intestines. We are not only fueled through digestion but our gut also influences many processes from head to toe. If our intestines are not functioning as they should, the entire body is affected.

Contents

Health begins in the gut!

This understanding dates back to the origins of medicine. The significance of the intestines as a hub for well-being was already recognised by Ayurvedic healers in their writings dating back 4000 years. Remarkably, modern science affirms this too! Our overall sense of well-being hinges on the proper functioning of our digestion. With trillions of microorganisms, the intestines regulate the majority of metabolic processes in our body, generate essential vitamins, enzymes, and amino acids, and counteract the harmful substances that enter our system through food.

Your Gut - The Centre of Health

What product suits you best?

Personalised Product Advice

Are you looking for the right multispecies probiotic for your health problems? Or are you looking for something specific? Then get in touch and consult our team of medical experts for a personalised recommendation for free!